- Pygoscelis

- Adélie penguin

- Chinstrap penguin

- Gentoo penguin

-

The Pygoscelis species often move in the water by way of porpoising,

which means that a penguin swims underwater with a speed of about 12 km/hour and

then jumps out of the water about every 30 à 50 m and flies half a second through the air, diving back again.

This short time is used to take a deep breath. Among other species this style of swimming rather means

they are in danger.

- The Pygoscelis species are sometimes called brush-tailed penguins, while their tail has very stiff feathers and stick out like on a brush.

- The 3 species of this group all make nests of stones.

- Two species (chinstrap and adelie) are migratory, while they leave their colony after breeding and stay away far at sea for months. Only the gentoo penguins mostly stay close (depending on their breeding place) to their nest and behave like sedentary birds.

- The 3 species belong to the cold sea penguins, meaning they live in polar or subpolar oceans.

- The Pygoscelis species are sometimes called brush-tailed penguins, while their tail has very stiff feathers and stick out like on a brush.

- The 3 species of this group all make nests of stones.

- Two species (chinstrap and adelie) are migratory, while they leave their colony after breeding and stay away far at sea for months. Only the gentoo penguins mostly stay close (depending on their breeding place) to their nest and behave like sedentary birds.

- The 3 species belong to the cold sea penguins, meaning they live in polar or subpolar oceans.

Adélie penguin - Pygoscelis adeliae

Adélies are the stereotype for a man in tuxedo. They have a white front and a black back. They have a very characteristic white ring around their eyes, which is most pronounced during the breeding season. The feathers on the back of their head are slightly longer and can be sticked up a bit. Juveniles are recognized by their white chin and they don't have the white ring yet. Small chicks have a uniform grey down.

The bill is short (characteristic for krill eaters), black with red.

Size and weight:

Adult adélies are around 73 cm tall.

Their weight varies during the year. Males weight between 4,4 and 5,4 kg; while females weight a bit less: between 3,9 and 4,8 kg.

Naming or nomenclature:

The Adélie penguin was firstly described by Hombron and Jacquinot in 1841, who used the Latin name "Catarrhactes adeliae".

Adélie penguins owe their name to a woman, who never set foot in Antarctica herself. When a French expedition, under leadership of captain Dumont dÚrville in 1840 reached the ice frontier, they discovered an island and named it after their captain. Later on land, they saw a little, fat penguin with a black coat and a white belly (like an apron), they named it Adélie, after their captain's wife. Afterwards, a complete region of Antarctica (Adélieland) was named after her.

Other languages:Nesting ground:

- Dutch: Adéliepinguïn

- German: Adéliepinguin

- French: manchot Adélie

- Spanish: pingüino de Adelia or de ojo blanco

- South African Dutch: Adéliepikkewyne

- Portuguese: Pinguim-de-adélia

Adélies breed on rocks all over the Antarctic continent. The total breeding population estimates more than 2,5 million pairs.

Status: stable, not in danger.

Breeding behaviour:

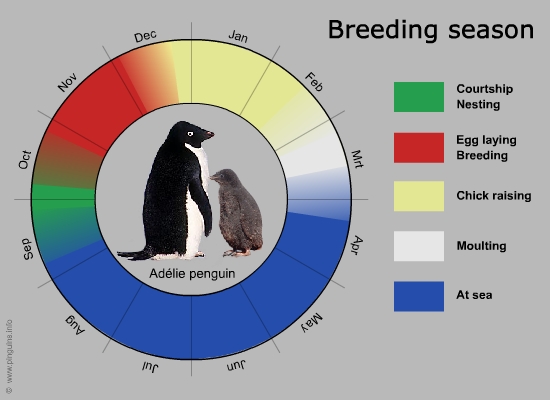

Adélie penguins build a rough nest of stones. They start breeding when they are between 3 till 8 years old. The males arrive in the colony in the first half of October, after walking tens (30-100) of kilometres over the pack ice. They nest close to each other between rocks, on hills and ridges in large colonies of up to thousands of pairs. As soon as they found a suitable nesting place, they start calling out loud to attract a female, with their bill up to the air and their flippers wide open. When a female reacts, they call together and bow for each other several times. (see sexual behaviour) Then mating follows.

End October-early November (6 till 10 days after female arrival), she lays two eggs, which will alternately be incubated by both parents during 32 till 34 days (in shifts of max 12 days).

After hatching, the chicks stay 22 days in the nest, where they are (also alternately) be guarded and fed by one parent or the other, till they are ready to congregate in crèches. Such crèche isn't large and mostly includes 10-20 chicks. The chicks are almost daily fed.

They moult to their juvenile plumage and fledge end January to early February when they are 50 à 60 days old. In the meanwhile it is summer on Antarctica and the pack ice is broken, so the chicks haven't to walk that far to open sea. Often you can see a chick with a little of down, standing on a floating iceberg or ice floe, while the chicks often leave before moulting is completed.

When the breeding period is over, the adult birds leave for a forage trip at sea for about ten days, before returning mid March to moult themselves. The moulting period lasts around 20 days.

Early April the colony is completely abandoned till early October a new breeding season begins. Many pairs are loyal for live and return each year to their same old nest.

Food:

Adélies feed almost exclusively on krill (99 % of their diet). Most of the time they forage on a depth between 10 till 40 metres, although their record is much deeper. They dive for fish during the daytime, when the light is the most bright under water. When feeding chicks, they stay close to the colony and return daily to the nest. After breeding they migrate far away from the colony and stay away for weeks.

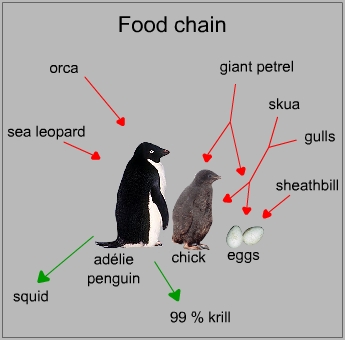

Predators:

The adult and juvenile birds are chased by orcas and leopard seals, especially during winter when they are most at sea. Chicks are robbed by giant petrels, skuas and other gulls. The sheath bill will try to steal the food, when an adult feeds its chick, and also cleans up the colony by eating dead penguins.

During the last years, a lot of chicks died of starvation, while icebergs block the way to sea for the adult birds, forcing them to take a longer road and causing delay.

Chinstrap penguin - Pygoscelis antarctica

Chinstrap penguins have a white front and face and a black back. They can be clearly distinguished by the small black line over their chin, therefore their name. They are very noisy and aggressive.

Apart of the royal penguin, which has a crest, it is the only species with a white face.

The first down of the chicks is grey, and juveniles have a grey back and a white front.

Size and weight:

Adult chinstrap penguins are 70 à 75 cm tall.

Their weight varies during the year, being the largest before moulting and the lowest when raising chicks.

Typical weight is 3,5 till 5 kg.

Naming or nomenclature:

Keelbandpinguïns or stormbandpinguïns are in Dutch alternative names for chinstrap penguins. According to an English naming they are also called sometimes "stonecrackers" because of the squeaky calls.

Firstly Forster used in 1781 the Latin name "Aptenodytes antarctica", but soon afterwards Gray named them Pygoscelis antarctica in 1844.

Other languages:

Nesting ground:

- Dutch: kinbandpinguïn or keelbandpinguïn or stormbandpinguïn

- German: Zügelpinguin

- French: manchot à jugulaire

- Spanish: pingüino de barbijo or pinguin de collar or de cara marcada

- South African Dutch: Stormbandpikkewyn or Keelstreeppikkewyn

- Portuguese: Pinguim-de-barbicha

Chinstrap penguins breed on sub-Antarctic islands and on the Antarctic Peninsula. They breed in very large colonies. There is a colony on the South Sandwich Islands with more than 10 thousand birds.

The total breeding population is estimated up to more than 7,5 million pairs.

Status: stable

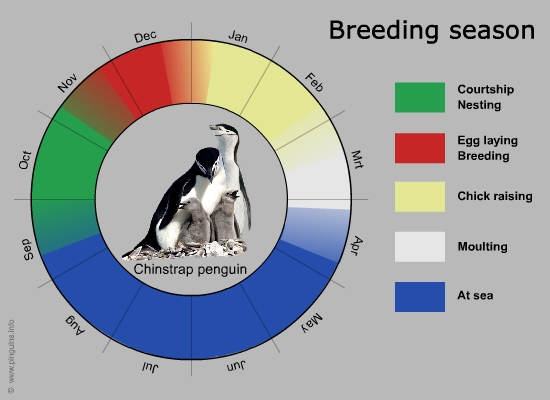

Breeding behaviour:

Chinstrap penguins build circular "stone nests", around 40 cm in diameter and 15 cm high in the centre. They prefer slopes, cliffs and ridges on ice free places. Sometimes they breed together with other Pygoscelis species, but on another level than the rest.

They arrive in the colony to court end September-November. Once pairs are made, the female lays 2 eggs in November-December which will be incubated by both parents in "shifts" of 5 à 10 days. The eggs hatch after 33 till 35 days and the chicks remain in the nest for another 20 à 30 days, before they gather in crèches. There they stay for some weeks, being fed daily.

The chicks moult to their juvenile plumage and leave the nest in end February-March after 50 à 60 days.

After the breeding period the adult birds leave too to forage at sea and return shortly after to moult in March-April. In the period between May till September the colony is abandoned and all the birds migrate to sea.

Food:

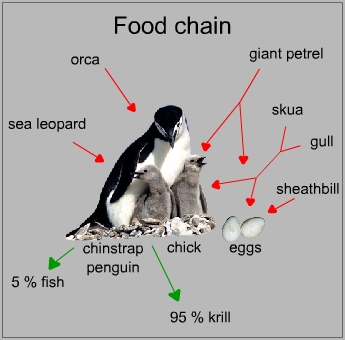

They mainly eat krill, complemented with about 5 % fish. They search for prey at daytime on depths of 10-40 metre (maximum 100 m) and during breeding they stay close to the shore and colony.

Predators:

While chinstrap penguins live in the same habitat as other Pygoscelis species, these adults too are chased by orcas (killer whales) and leopard seals. Chicks are prey to giant petrels, skuas and other gulls, and eggs are stolen by gulls and sheath bills.

Gentoo penguin - Pygoscelis papua

Gentoo penguins are easily recognized by the broad white stripe which runs over the top of their head. It is the largest and most peaceful among the Pygoscelis species. They are the most widespread and timid. They have an orange bill and long, stiff feathers on their tail which stick out when they walk.

Chicks have a grey back and a white front. Two subspecies are known: the P. p. papua and the smaller P. p. ellsworthi.

Size and weight:

Adult gentoo penguins reach a height up to 75 till 80 cm.

Males have their max weight of around 8 kg right before moulting, and minimum of 5,5 kg just before mating. For females this maximum is 7,5 kg before moulting, and the minimum goes under 5 kg when taking care for their chicks in the nest.

Naming or nomenclature:

Two subspecies are recognized: the P. p. papua and the smaller P. p. ellsworthi.

The gentoo penguin was first described by Sonnerat in 1776, who spoke of Manchot papou. The gentoo penguin got its scientific name (papua) while they thought by mistake to have seen this species in Papua/New Guinea.

Forster used in 1781 the scientific name "Aptenodytes papua", and the subsequent name "Pygoscelis papua" derives from Wagler in 1832.

Gentoo seems to be an archaic word for Hindu, the white marks on the bird's head apparently reminding early voyagers of a turban. Sealing crews referred to it as Johnny penguin.

Other languages:

Nesting ground:

- Dutch: ezelspinguïn

- German: Eselspinguin

- French: manchot papou

- Spanish: pingüino de Pico Rojo of papúa of juanito

- South African Dutch: Witoorpikkewyn or Eselpikkewyn

- Portuguese: Pinguim-gentoo

Gentoo penguins breed on many sub-Antarctic islands. The most important colonies are on the Falklands, South Georgia and the Kerguelen islands. Smaller groups are found on Macquarie eiland, Heard Islands, South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula.

The total population is estimated to up to 314 000 pairs.

On the map: light yellow circles mean the habitat of the subspecies P. p. papua and the orange circles indicate P. p. ellsworthii.

Status: vulnerable (smaller risk), (2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species)

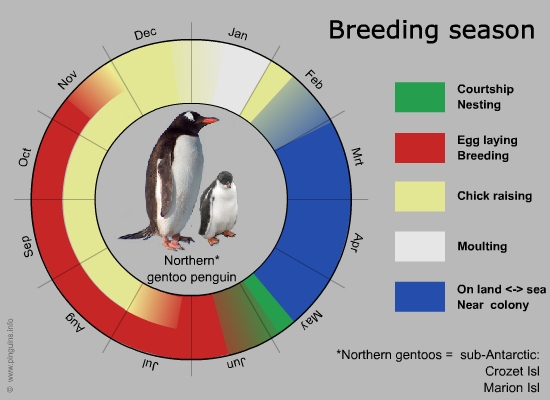

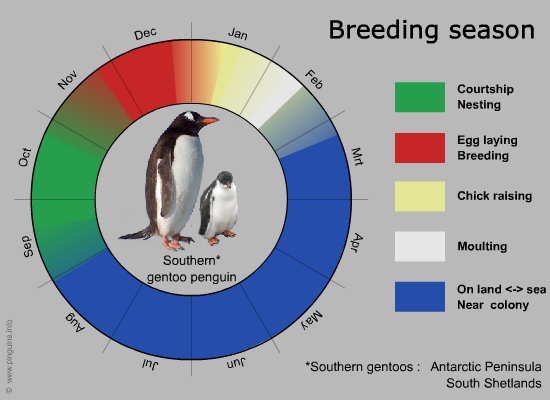

Breeding behaviour:

There is a large time interval between the northern and southern species. The northern subspecies starts breeding a lot earlier (May-June) than the southern subspecies (September-October) on the Antarctic Peninsula and the South Shetlands, where it is a lot colder and the winter lasts longer.

But the colonies are never completely abandoned while gentoo penguins stay close to the colony even in winter, and often appear there.(semi sedentary birds) The nests are made of a rough, circular pile of stones, with a size of 20 cm high and 25 cm in diameter. (see also breeding nest)

Two eggs are laid, each about 130 gr. Both parents alternate daily during incubation. Chicks hatch after 34 à 36 days. The chicks stay in the nest during 30 days, before joining a small crèche.

The chicks moult to juvenile plumage and go to sea (fledge) after 80 à 100 days. In the southern colonies they fledge in February, among the northern gentoos it can be a lot earlier when the pair started breeding early in the season.

Among the northern gentoos, where the breeding season lasts much longer, chicks of all stages can be found, but among the southern gentoos it all happens much more simultaneous.

Food:

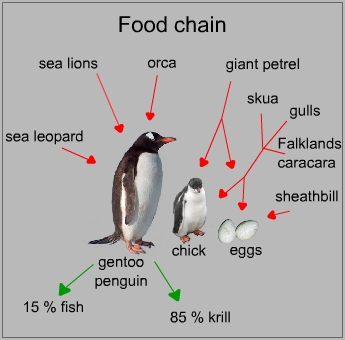

Gentoo penguins feed almost only on crusteceans like krill, with fish being only a small part (around 15 %) of their diet. The moderate diving depth is between 40 and 110 metre, with a maximum of 170 metre.

They hunt at day time, off the coast and close to their nest. During breeding season they forage at shallower depths and return much more often to their nest to feed their chicks.

Predators:

At sea, the southern gentoos mainly have to suffer of leopard seals and orcas, while the northern gentoos are chased by sea lions too.

Chicks die through giant petrels, skuas and gulls, and on the Falklands birds of prey like caracaras will steal chicks and eggs too.

© Pinguins info | 2000-2021