- Aptenodytes

- Emperor penguin

- King penguin

- Largest penguins, including 2 species: the emperor penguins and king penguins.

They can slightly be confused while they both have a patch on their throat and chin.

But the patch of the emperor is pale yellow and open, while it on the king penguin two closed orange patches are.

Moreover emperor penguins are taller and heavier and only live on the Antarctic ice, while king penguins

live much more up north. So you can be sure to see a king penguin when you visit the Falklands and not an emperor,

and if you are in Antarctica it will be the opposite. (see also characteristics)

- Those 2 species are the only penguins which lay just one egg and don't build a nest. They incubate the egg on their feet, against a bare brood patch on their belly, under a fold of skin covered with feathers. The chick too will be kept warm there, till it is able to regulate its own warmth insulation. Still there is a lot of difference between the breeding behaviour of both species.

- Both species belong to the cold sea penguins, meaning they live in polar or sub polar oceans.

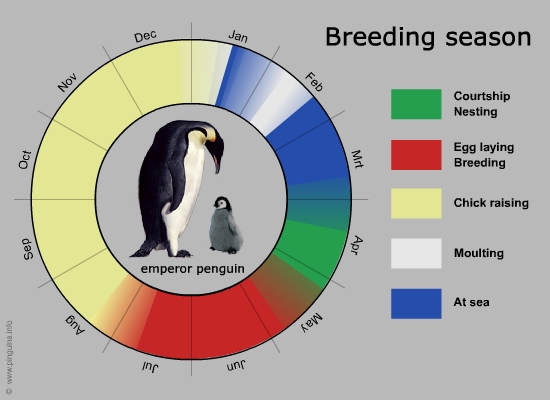

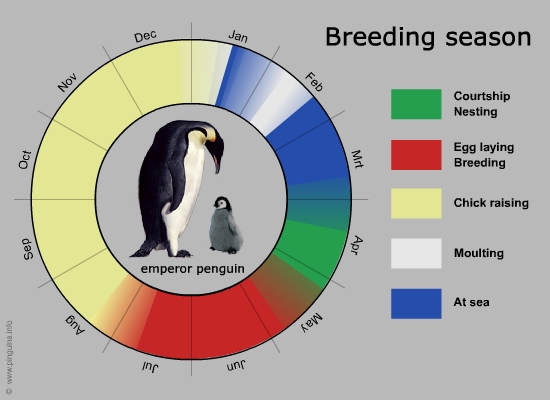

- Both species are migratory, while emperors move north at sea during southern summer (Jan-March) and king penguins leave the colony and go south at sea for feeding during the long winter (May-Aug).

- Those 2 species are the only penguins which lay just one egg and don't build a nest. They incubate the egg on their feet, against a bare brood patch on their belly, under a fold of skin covered with feathers. The chick too will be kept warm there, till it is able to regulate its own warmth insulation. Still there is a lot of difference between the breeding behaviour of both species.

- Both species belong to the cold sea penguins, meaning they live in polar or sub polar oceans.

- Both species are migratory, while emperors move north at sea during southern summer (Jan-March) and king penguins leave the colony and go south at sea for feeding during the long winter (May-Aug).

Emperor penguin - Aptenodytes forsteri

Specific characteristics: sound (mp3)

This is the largest species of penguins. Emperor penguins are only found on and around the Antarctic continent, on the thick pack ice and rarely on mainland. They have a pale yellow, open (breast and chin patch are one) patch on chin and breast. A long, thin and curved bill, typical for fish eaters. Very dark grey back and blue black head. Chicks are silver grey with black head and white face.

Size and weight:

Adult emperor penguins are up to 1,2 m tall.

Juvenile emperors are remarkable smaller with a size of 90 cm à 1 m.

They weight between 30 and 40 kg, with great fluctuations during the year. Males can lose up to half of their weight, while incubating their egg.

Naming or nomenclature:

The emperor penguin was first described after an expedition by Sir James Clark Ross in 1844.

Emperor penguins owe their scientific name (Aptenodytes forsteri) to their discoverer, the first natural scientist to reach Antarctica, the German Johann Reinhold Forster. Forster came to Antarctica in 1770, on Captain James Cook's ship, and saved Cook's life during the voyage. Cook was weakened by hunger and cold. Forster served him fresh meat bouillon although there was only rusk on board. But when Cook recovered, the ship's dog was missing. Maybe that's the reason why the emperors were named for their appearance rather than their discoverer.

Other languages:

Emperor penguins breed on the permanent ice on Antarctica, till up to more than 100 km of the edge.

They rarely set foot on the mainland, but stay on the ice. The total breeding population is estimated at 170 million pairs. More than a quarter of the total population breeds on the Ross sea, and one colony can contain up to 20 thousand pairs.

Status: stable, not in danger.

Breeding behaviour:

Emperor penguins have a very extreme breeding behaviour.

It is the only species that breeds during the Antarctic winter. Before reaching their breeding "ground", in March-April they have to walk for up to 100 km over the ice. This sea ice is formed every winter around April and melt away in the austral summer (December-January). Therefore they have to breed far from the edge, to avoid it would melt under their feet before the chicks are ready to fledge.

Most of the colonies are situated under the shelter of icebergs or cliffs. The female lay one single egg in May, and directly pass it on to the male, who will incubate it on its own during the Antarctic winter (June-August and at minus 70 °C) for 64 days on its feet. For protection against the cold and icy weather all breeding males huddle together in a large group. They slowly rotate in a circular way, so every male on its turn has a chance to warm up in the centre and has to bear the storms at the outside.

By the time the chick hatch (August), the females return to feed it. If it takes too long before the female arrives, the male will still be able to throw up a kind of "porridge" as a first meal for the chick. It is amazing how they can do it, knowing they had no food at all during the period of walking, courting and incubation (3 months). But then the emaciated males must go to sea, or they would starve. If the female isn't back, the male will abandon the chick to save its own life. If the female arrives in time, she will guard the chick for some weeks (24 days). After 40 days the chick will be able to resist the cold and huddle together in crèches. Now both parents alternate to feed the chick. In the meanwhile it is spring and the ice has melt away, so the distance to the edge is much shorter and the adults can come and go much faster. Early November the chick will moult to its juvenile plumage.

The chick fledge in December-January (early summer) when it is 120 till 150 days old. They weight just half as much as the adults, but while it is the summer, there is plenty of food and they will grow very fast.

They become sexually mature around 5 à 6 year.

The adult birds moult in February for 30 days, after a period of feeding up at sea.

Food:

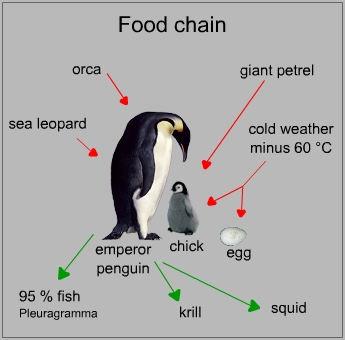

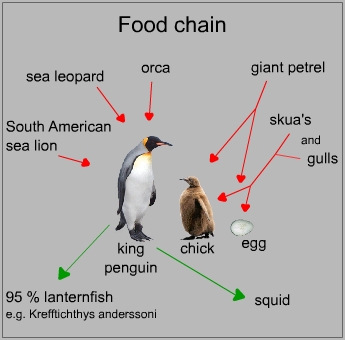

They eat several fish (mainly Pleuragramma) with a complement of crusteceans like krill.

They hunt at a depth till 150 m under the ice for krill and crusteceans and between 400 and 450 m for fish and squid. They can stay under water for 2 till 9 minutes, but their record is 565 m depth and uninterrupted 18 min under water.

Predators:

While breeding in the winter, eggs and chicks have little to suffer of birds. Most of the time, only the giant petrel will steal a careless chick. But the icy cold is often fatal for eggs and chicks: while passing on the egg, it has to happen very quickly or the egg will be frozen. The first weeks after hatching, chicks which escape from under the brood patch, will soon freeze to death. And while non-breeders, or birds who lost their own, will try to steal the egg or chick of another bird, but abandon it after a short time, the mortality rate is high.

In the water leopard seals and orcas are predators to adult and juvenile birds.

This is the largest species of penguins. Emperor penguins are only found on and around the Antarctic continent, on the thick pack ice and rarely on mainland. They have a pale yellow, open (breast and chin patch are one) patch on chin and breast. A long, thin and curved bill, typical for fish eaters. Very dark grey back and blue black head. Chicks are silver grey with black head and white face.

Size and weight:

Adult emperor penguins are up to 1,2 m tall.

Juvenile emperors are remarkable smaller with a size of 90 cm à 1 m.

They weight between 30 and 40 kg, with great fluctuations during the year. Males can lose up to half of their weight, while incubating their egg.

Naming or nomenclature:

The emperor penguin was first described after an expedition by Sir James Clark Ross in 1844.

Emperor penguins owe their scientific name (Aptenodytes forsteri) to their discoverer, the first natural scientist to reach Antarctica, the German Johann Reinhold Forster. Forster came to Antarctica in 1770, on Captain James Cook's ship, and saved Cook's life during the voyage. Cook was weakened by hunger and cold. Forster served him fresh meat bouillon although there was only rusk on board. But when Cook recovered, the ship's dog was missing. Maybe that's the reason why the emperors were named for their appearance rather than their discoverer.

Other languages:

Nesting ground:

- Dutch: keizerspinguïn

- German: Kaiserspinguin

- French: manchot empereur

- Spanish: pingüino emperador

- South African Dutch: Keiserpikkewyn

- Portuguese: Pinguim-imperador

Emperor penguins breed on the permanent ice on Antarctica, till up to more than 100 km of the edge.

They rarely set foot on the mainland, but stay on the ice. The total breeding population is estimated at 170 million pairs. More than a quarter of the total population breeds on the Ross sea, and one colony can contain up to 20 thousand pairs.

Status: stable, not in danger.

Breeding behaviour:

Emperor penguins have a very extreme breeding behaviour.

It is the only species that breeds during the Antarctic winter. Before reaching their breeding "ground", in March-April they have to walk for up to 100 km over the ice. This sea ice is formed every winter around April and melt away in the austral summer (December-January). Therefore they have to breed far from the edge, to avoid it would melt under their feet before the chicks are ready to fledge.

Most of the colonies are situated under the shelter of icebergs or cliffs. The female lay one single egg in May, and directly pass it on to the male, who will incubate it on its own during the Antarctic winter (June-August and at minus 70 °C) for 64 days on its feet. For protection against the cold and icy weather all breeding males huddle together in a large group. They slowly rotate in a circular way, so every male on its turn has a chance to warm up in the centre and has to bear the storms at the outside.

By the time the chick hatch (August), the females return to feed it. If it takes too long before the female arrives, the male will still be able to throw up a kind of "porridge" as a first meal for the chick. It is amazing how they can do it, knowing they had no food at all during the period of walking, courting and incubation (3 months). But then the emaciated males must go to sea, or they would starve. If the female isn't back, the male will abandon the chick to save its own life. If the female arrives in time, she will guard the chick for some weeks (24 days). After 40 days the chick will be able to resist the cold and huddle together in crèches. Now both parents alternate to feed the chick. In the meanwhile it is spring and the ice has melt away, so the distance to the edge is much shorter and the adults can come and go much faster. Early November the chick will moult to its juvenile plumage.

The chick fledge in December-January (early summer) when it is 120 till 150 days old. They weight just half as much as the adults, but while it is the summer, there is plenty of food and they will grow very fast.

They become sexually mature around 5 à 6 year.

The adult birds moult in February for 30 days, after a period of feeding up at sea.

Food:

They eat several fish (mainly Pleuragramma) with a complement of crusteceans like krill.

They hunt at a depth till 150 m under the ice for krill and crusteceans and between 400 and 450 m for fish and squid. They can stay under water for 2 till 9 minutes, but their record is 565 m depth and uninterrupted 18 min under water.

Predators:

While breeding in the winter, eggs and chicks have little to suffer of birds. Most of the time, only the giant petrel will steal a careless chick. But the icy cold is often fatal for eggs and chicks: while passing on the egg, it has to happen very quickly or the egg will be frozen. The first weeks after hatching, chicks which escape from under the brood patch, will soon freeze to death. And while non-breeders, or birds who lost their own, will try to steal the egg or chick of another bird, but abandon it after a short time, the mortality rate is high.

In the water leopard seals and orcas are predators to adult and juvenile birds.

King penguin - Aptenodytes patagonicus

Specific characteristics:

This is the second largest species. They have more orange closed patches on the upper breast and another one on the cheek. They have a slightly longer, more curved bill than the emperor. Their back is dark silver grey and the head is black. The chicks are uniform brown and can grow taller than their parents. Early discoverers thought the chicks were a different species.

Size and weight:

Adult birds are 90 cm tall.

Both sexes weigth 15 à 16 kg at the begin of the breeding season, but females lose more weight, so males weight at the end of the season 13 kg and females around 11 kg.

Naming or nomenclature:

Two subspecies can be distinguished: the A. p. patagonicus on South Georgia and the Falkland Islands, and the A. p. halli on the Kerguelen, Crozet, Heard, Prins Edward and Macquarie islands. There are some differences between the populations on the several islands, while they live genetically isolated.

The king penguin was first described by Pennant in 1768.

Other languages:

King penguins breed in large colonies on several sub Antarctic islands.

Worth mentioning are the colonies on Crozet Island, Prince Edward Island, Kerguelen Island, South Georgia and Macquarie Island.

The total breeding population is estimated at one million pairs.

Status: stable, not in danger.

The breeding ground of the 2 subspecies are on the map marked with different colours: A. p. patagonicus is light yellow and orange indicates A. p. halli.

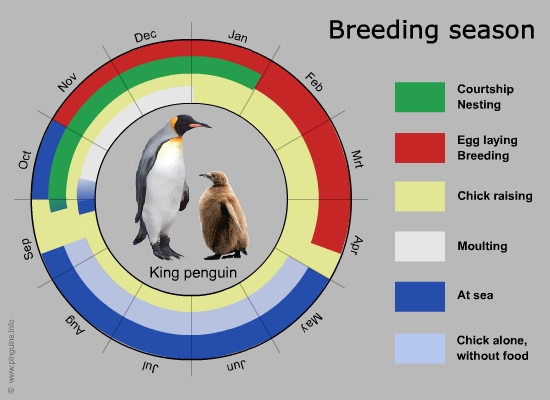

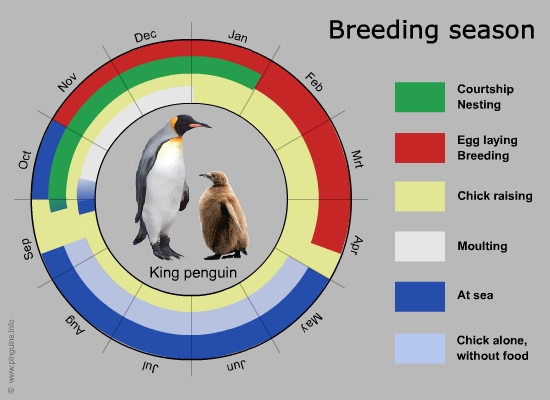

Breeding behaviour:

King penguins have a unique breeding cycle. It takes 14 till 16 months to court, lay an egg and raise a chick. Most pairs therefore raise a chick just twice in a period of three years. In a colony chicks of every age will live side by side. A pair that laid an egg in November (early summer) in the first breeding season, has to go on raising it after the next winter (May-August) in September. Only the next year in February-March (near the end of the second breeding season) they will again lay one egg. With a bit of luck the chick has grown enough before the next winter to survive. Adults with smaller chicks return more often to feed it during the winter. It will be raised further in the next (third breeding season) summer. But when that second chick is ready to fledge, it is too late in the season to start breeding again. The adults therefore leave the colony and lay an egg not until the next (fourth) breeding season.

The breeding cycle starts when the adult birds come ashore to moult and then return to sea for 20 days to regain energy. They breed on flat beaches or in valleys close to the water and under the shelter of high bunches, as protection against the wind. The female lays one single egg, which will be incubated for 54 days by both alternating parents. They incubate the egg, and later the chick, on their feet, against a bare brood patch on their belly, under a fold of skin covered with feathers. The chick remains 30 till 40 days on that place, until it is old enough to regulate its body temperature and can go to the crèche. Now both parents will forage and feed the chick. During the long winter period (May-August) chicks will only be fed once till maximum three times. Only the strongest will survive the winter. The chicks moult to their juvenile plumage and fledge at the age of around 13 months.

(see pictures of a King penguin with egg)

Food:

King penguins eat almost only lanternfish, with very rarely a squid or crusteceans.

Frequently, they stay at sea for a few days and dive, by day, to depths between 100 and 300 metre, in search for fish. At night, they go fishing too but then at a shallow depth (max. 30 metre). Firstly while they see less at night, but then lanternfish come a lot closer at the water surface. Breeding birds will stay close(1 à 30 km) to their breeding ground, while non breeders go much further away.

Predators:

King penguins are often chased and killed by orcas and leopard seals. And birds who have to walk through a group of sea lions to reach the water, sometimes are crushed to death by mutual fights of those sea lions. Or sea lions catch the birds at the bay, on their way to or from the nest. The smaller chicks and eggs are robbed by giant petrels, skuas and other gulls. Especially during the winter, a lot of the weakened chicks die that way.

This is the second largest species. They have more orange closed patches on the upper breast and another one on the cheek. They have a slightly longer, more curved bill than the emperor. Their back is dark silver grey and the head is black. The chicks are uniform brown and can grow taller than their parents. Early discoverers thought the chicks were a different species.

Size and weight:

Adult birds are 90 cm tall.

Both sexes weigth 15 à 16 kg at the begin of the breeding season, but females lose more weight, so males weight at the end of the season 13 kg and females around 11 kg.

Naming or nomenclature:

Two subspecies can be distinguished: the A. p. patagonicus on South Georgia and the Falkland Islands, and the A. p. halli on the Kerguelen, Crozet, Heard, Prins Edward and Macquarie islands. There are some differences between the populations on the several islands, while they live genetically isolated.

The king penguin was first described by Pennant in 1768.

Other languages:

Nesting ground:

- Dutch: koningspinguïn

- German: Königspinguin

- French: manchot royal

- Spanish: pingüino rey of pinguin real

- South African Dutch: Koningpikkewyn

- Portuguese: Pinguim-rei

King penguins breed in large colonies on several sub Antarctic islands.

Worth mentioning are the colonies on Crozet Island, Prince Edward Island, Kerguelen Island, South Georgia and Macquarie Island.

The total breeding population is estimated at one million pairs.

Status: stable, not in danger.

The breeding ground of the 2 subspecies are on the map marked with different colours: A. p. patagonicus is light yellow and orange indicates A. p. halli.

Breeding behaviour:

King penguins have a unique breeding cycle. It takes 14 till 16 months to court, lay an egg and raise a chick. Most pairs therefore raise a chick just twice in a period of three years. In a colony chicks of every age will live side by side. A pair that laid an egg in November (early summer) in the first breeding season, has to go on raising it after the next winter (May-August) in September. Only the next year in February-March (near the end of the second breeding season) they will again lay one egg. With a bit of luck the chick has grown enough before the next winter to survive. Adults with smaller chicks return more often to feed it during the winter. It will be raised further in the next (third breeding season) summer. But when that second chick is ready to fledge, it is too late in the season to start breeding again. The adults therefore leave the colony and lay an egg not until the next (fourth) breeding season.

The breeding cycle starts when the adult birds come ashore to moult and then return to sea for 20 days to regain energy. They breed on flat beaches or in valleys close to the water and under the shelter of high bunches, as protection against the wind. The female lays one single egg, which will be incubated for 54 days by both alternating parents. They incubate the egg, and later the chick, on their feet, against a bare brood patch on their belly, under a fold of skin covered with feathers. The chick remains 30 till 40 days on that place, until it is old enough to regulate its body temperature and can go to the crèche. Now both parents will forage and feed the chick. During the long winter period (May-August) chicks will only be fed once till maximum three times. Only the strongest will survive the winter. The chicks moult to their juvenile plumage and fledge at the age of around 13 months.

(see pictures of a King penguin with egg)

Food:

King penguins eat almost only lanternfish, with very rarely a squid or crusteceans.

Frequently, they stay at sea for a few days and dive, by day, to depths between 100 and 300 metre, in search for fish. At night, they go fishing too but then at a shallow depth (max. 30 metre). Firstly while they see less at night, but then lanternfish come a lot closer at the water surface. Breeding birds will stay close(1 à 30 km) to their breeding ground, while non breeders go much further away.

Predators:

King penguins are often chased and killed by orcas and leopard seals. And birds who have to walk through a group of sea lions to reach the water, sometimes are crushed to death by mutual fights of those sea lions. Or sea lions catch the birds at the bay, on their way to or from the nest. The smaller chicks and eggs are robbed by giant petrels, skuas and other gulls. Especially during the winter, a lot of the weakened chicks die that way.

© Pinguins info | 2000-2021